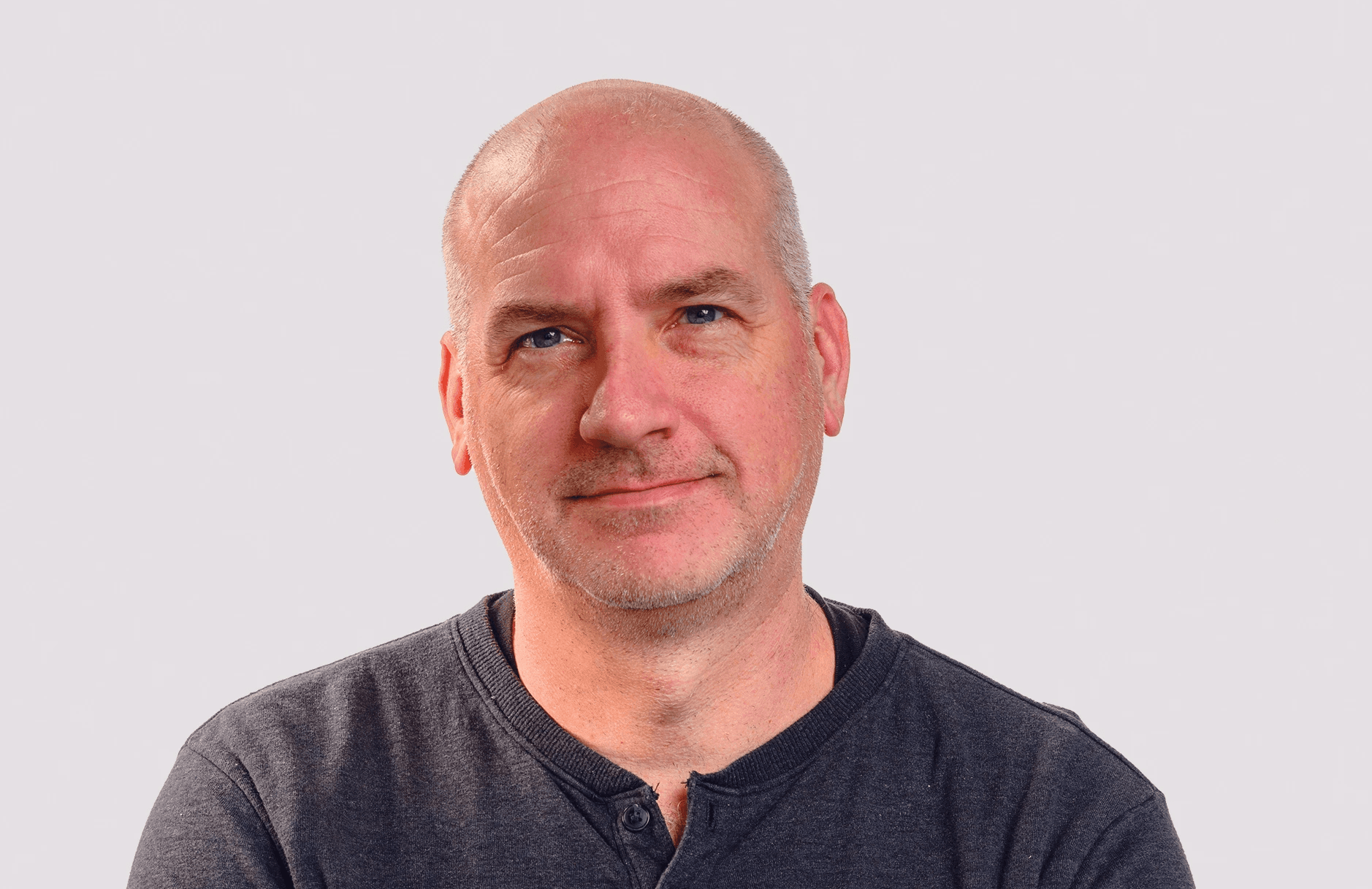

BRIAN ULASZEWSKI

BEYOND BLUEPRINTS: PUBLIC INTEREST DESIGN AND THE POWER OF COMMUNITY AGENCY

L*OSMONAUTA #0005

/

15 min read

Brian Ulaszewski is the Executive Director and Principal of City Fabrick, guiding the organisation’s collective vision, care and creativity. Leveraging policymaking, planning and design, he helps communities co-create solutions and shape their own futures. Recognised with the John Chase Visionary Award, he also teaches at the University of Southern California. He enjoys travelling, exploring new culinary experiences and practising mixology for family and friends.

Interview :

BRIAN ULASZEWSKI

Executive Director and Principal of City Fabrick

We were really curious to dive deeper, especially because what you do with City Fabrick feels much closer to the kind of dynamics we experience in Europe, rather than the more typical narratives we hear coming out of the U.S. So if you had to explain City Fabrick to someone completely outside this world say, a teenager or an older couple, how would you describe what you do?

Honestly, it’s always a challenge to communicate what we do clearly, whether through a website or even just a quick elevator pitch. One of the first questions people ask is, “What’s your short intro to City Fabrick?” And I usually share our mission: we’re a nonprofit urban design studio focused on reshaping, restoring, and empowering communities through public interest design, planning, policy development, and advocacy.

But honestly, that’s just a long-winded way of saying, we’re here to help, and we help in a lot of different ways. If you go to an architecture firm, you get an architectural solution. If you go to a landscape architecture firm, you get a landscape solution. For us, sometimes it’s a can of paint, sometimes it’s removing infrastructure, sometimes it’s a website, a flyer, or building a new building.

We don’t come in with a fixed idea of what the solution should be, it really depends on what the community needs.

Actually, there's a longer tradition in the States of what we call community design centers, which really started gaining traction in the 1960s and ’70s. A lot of those were connected to universities and were often run by faculty members who were still semi-active in practice. They’d set up studios that brought in students through hands-on, applied learning classes, urban design projects, architectural interventions, always rooted in local community engagement.

City Fabrick isn't the only nonprofit design studio in the U.S. There are a few others, especially around the LA area. One of the more well-known ones right now is MASS Design, based in Boston.

One of the most famous examples is probably the Rural Studio at Auburn University. There, students would go out into rural communities and design and build homes for people who otherwise didn’t have access to stable housing. It’s an amazing model. Some of those initiatives are still around today, though many have faded over the years.

Building on what you shared about City Fabrick’s origins and your early community projects like Gumbiner Park, could you tell us more about how it all started

The idea of a nonprofit design studio really came into focus when I was working at a traditional urban design firm, doing the usual mix: mixed-use developments, commercial buildings, and some city planning. But I was also deeply involved in my own community, which was facing big challenges, lack of parks, underdeveloped infrastructure, and environmental justice issues.

I started using my creativity to find solutions: adding green space, improving traffic safety. Gumbiner Park was one of the first projects where I applied this thinking as a resident.

Gradually, I shifted my portfolio toward projects aligned with that mission, affordable housing, collaborations with nonprofits and local governments.

But community advocacy wasn’t always welcomed, especially since our local government, sometimes my former firm’s client, didn’t always appreciate it. During the Great Recession, a community partner, later a founding board member, told me, “You’ve already created enough work to start your own firm.” I didn’t want just another firm, but I knew I wanted something different.

That’s when I explored community design centers and found a model we could adapt. In Long Beach, surrounded by LA and Orange County, there wasn’t a strong network of designers and planners offering skills to communities in need. That’s what sparked City Fabrick.

With initial support from the California Endowment, we started with advocacy, research, and educational programming. But grants weren’t enough, so we developed a social enterprise model: offering services to affordable housing developers, nonprofits, and local governments. This balanced approach, grants, fee-for-service, surplus revenue, allowed us to grow.

We began as just me and a talented graphic designer, and now we have a team of architects, landscape architects, planners, and designers. Our work ranges from public space design to branding.

That’s the short version of how City Fabrick came to be.

When it comes to your current projects, do they usually start from your own observations and proposals, or are you now more often approached directly by communities or institutions? And how do collaborations, with local groups, nonprofits, or government, shape the way City Fabrick operates?

In the early days, our work was much more about proposing interventions, planting the seed and trying to get something off the ground. We were often the ones initiating the conversation, identifying opportunities, and pushing for action.

Today, it's become a more dynamic and varied process.

In some cases, we're brought in when there's already the essence of an idea in place, and our role is to help shape it into something concrete and actionable.

Other times, a partner will bring us into a project, maybe involving a specific property or a community, and while there’s energy and engagement, there’s not yet a clear vision of what the intervention should be. It's not a blank canvas, because we don’t work on untouched or undeveloped land, but it is an open space where the community is active, our partners are committed, and we’re all working together to define the solution.

For example, on one end of the spectrum there's Gumbiner Park, which you mentioned earlier. In that case, the community had identified a clear need, there was a lack of public open space and significant safety concerns in the area. We developed a concept around those issues and helped bring it to life. That’s a case where the intervention really started with us, responding directly to community needs.

At the other end of the spectrum, we’ll get involved in more conventional urban design projects, like when a partner comes to us with a site and a specific goal, such as developing a certain number of affordable housing units along with community amenities. In those cases, the framework is already defined, and our role is more technical and design-focused.

Then there’s this third, more open-ended space, like the collaboration we’re currently starting with the City of Compton. They have dozens of vacant parcels scattered throughout the community and a clear need for more park space. But there’s no fixed brief yet. So we're working with them to analyze where the needs are greatest, where the opportunities lie, and how to create a more connected, equitable network of public and open spaces. It’s a very collaborative, strategic process that evolves as we engage with both the city and the community.

We are also having to lean into the current conditions of our federal government, using our creative and technical capacity to oppose freeways expansions, immigrant interment camps, and ghettoization. It puts our organization at risk but we cannot sit on the sidelines during these times.

In projects like the one in Compton, or others you've mentioned, are everyday residents, people actually living in the neighborhood, actively involved in the process? And why is that kind of participation so essential to the way City Fabrick approaches planning and design? What kind of tangible outcomes does it lead to?

That’s always our main effort, to truly engage community members. While we bring creativity and technical expertise in planning public spaces, there’s a wealth of grounded, local knowledge that we simply don’t have.

That local expertise is essential to make the projects meaningful and successful.

For example, in North Long Beach, we worked on an open space plan aimed at filling gaps in the existing park network. This is a fully built-out community with very few vacant properties, so we had to get creative by leveraging existing infrastructure, civic sites, streets, freeways, even flood control facilities.

We organized a series of workshops across the community where we shared inspiring case studies from other cities, everything from river naturalization projects to Portland’s famous Burnside Skatepark, which is cleverly located under a freeway overpass. We presented these ideas alongside maps of the local area showing where natural and built features like rivers and freeways were, helping residents see their neighborhood from a fresh spatial perspective.

One of the most popular proposals came directly from community members. They suggested extending a park under a freeway overpass to connect two neighborhoods that were otherwise divided. Initially, not everyone was on board for instance, one nearby resident was quite skeptical and even vocal about it during outreach. But another neighbor pointed out that this idea actually came from someone in the community named Paul, reminding her about the meetings she hadn’t attended.

By the next meeting, she had completely changed her tune and was excited about the project, even asking when construction would begin.

This story really highlights how powerful it is when people take ownership of ideas, they become the strongest advocates for their own community’s transformation.

There are many examples like this where the best ideas in our urban design plans didn’t come from us. Instead, we provide the tools and support to help communities think creatively and envision their surroundings in new, inspiring ways.

Absolutely, it’s not about finding the “right” answer, but helping people to think critically and imagine possibilities. The value lies in the process, getting there on their own.

I once read about a project that used Minecraft to involve youth in urban planning in African slums. It was brilliant, by using a familiar tool, they made the abstract tangible, and that made all the difference.

It really shows how powerful it can be to frame planning in familiar, accessible ways. Have you ever used tools like that, maybe not digital, but anything that helps people intuitively connect with and reimagine their environment?

Absolutely. It’s all about meeting people where they are and using familiar formats as a bridge into reimagining their environment. We haven’t used video games ourselves, but we’ve designed board games for park visioning projects, and they’ve proven to be incredibly effective.

We’ll create a board that mirrors their local park, with a grid layout and tokens representing different amenities, like basketball courts, community gardens, or outdoor fitness equipment. Everyone gets a set budget to “spend,” but it’s never enough to get everything they want, so they have to collaborate. Maybe a few neighbors pool their budgets to build a shared basketball court, for example, and then together decide where it should go.

Once the initial layout is done, we shift to role-playing: we hand out lanyards that assign participants new identities, someone becomes a park ranger, another a parent with a stroller, a teenager, a senior citizen. They then revisit the layout and are asked: “Does this work for me now? Does the park feel safe, accessible, and welcoming from this perspective?” It builds empathy, consensus, and often leads to key design changes.

It’s low-tech, but that’s often the beauty of it.

It’s accessible, tangible, and it gives people agency in a process they might otherwise feel excluded from.

That's really interesting. How do local communities usually respond when you propose these kinds of participatory approaches? Are they generally open to engaging in the process?

Institutional partners like local park agencies usually see the value in what we do. They want to engage communities but often struggle to find the right language or setting. When we propose interactive, playful approaches, they usually get it. Sometimes they want to see a prototype first, so we test and refine along the way.

Community members mostly respond positively. There can be initial skepticism—people come in with fixed ideas like “I want the basketball court here” or “No skate park.” But once they start the process, that usually softens. I recall an older man who didn’t want anything that would attract young people. He chose walking paths and gardens during the game. Then I gave him a lanyard role as a parent with a child, and it made him think differently. In the end, he placed a playground, just on the opposite side of the park from his house!

The gamification makes it fun, which is important since people give up their own time. If it’s not engaging or meaningful to us, why should it be for them?

We always ask ourselves: Is this worth their time? Does it resonate? That’s how we make sure our work connects.

How do you manage to effectively engage different groups within the same community, especially when their interests and ways of participating can be so different?

That’s actually something we do in a lot of different communities, but a good example is our recent work in Downtown Long Beach, where we’ve been doing engagement around updating their downtown plans. One of the tools we’ve developed is a mini-grant program. So, alongside organizing broader community workshops, we also partnered with around 20 different community groups. Each of them received a mini-grant to host their own events.

We would plug into those events, but the groups themselves really drove the direction of the activity, tailoring it to the people they know best. Different groups have different stakeholders, and those individuals respond to different types of engagement. We all shared a common goal: gathering meaningful input, but the approach we took to achieve it looked very different from one group to the next.

It worked well. It gave us a much deeper reach into the community and also gave those community partners a stronger sense of ownership in the process and the outcome. On top of that, it helped us become more culturally literate and thoughtful about how we engage with different groups and residents.

You mentioned earlier your work in affordable housing, do these kinds of participatory and community-centered approaches also carry over into those projects? Or do they tend to follow a more traditional path in terms of process and design? How does City Fabrick’s philosophy translate when it comes to housing?

It really depends on the context. In some cases, like when we’re working on master plans for existing affordable housing communities, looking at renovations or expansions, the process feels very similar to what I was describing earlier, with strong engagement and shared visioning. But other times, we’re working with a partner and a public agency to develop affordable housing on a vacant lot in an existing neighborhood, and the dynamics can be completely different.

We do try to bring in the same participatory approach, especially when there are shared ground-floor uses or open space amenities that can benefit the broader community. But we’ve also faced strong resistance, classic NIMBY situations, where people simply don’t want affordable housing in their neighborhood.

In those cases, our role becomes more about “defend and adapt.” We still meet with the community, we listen to their concerns, especially those related to design, scale, and traffic, and we try to reflect those where possible. But when the opposition is based on stereotypes or exclusionary attitudes, like, “We don’t want those people here”, we acknowledge that perspective but stand firm in explaining the regional need for affordable housing.

There was one case I remember clearly: we were proposing to redevelop a tired old strip mall. It had a big parking lot and a closed gas station on the corner. The plan was to keep the local businesses, renovate the storefronts, add outdoor spaces like a walking loop and plaza, and build new affordable housing with space for a community partner on the ground floor. The response? “We like everything except the housing, could you build a parking garage instead?”

They were concerned about overcrowding and people living in converted garages, so we asked, “Wouldn’t it be better to build actual housing so those garages can be used for parking again?” But that logic didn’t really land.

Still, we adjusted the design, incorporated some community input, added traffic safety measures, and we moved forward. At the public hearings, some residents even acknowledged that we had listened and improved the plan, even if they still opposed the housing itself. But then, at the ribbon cutting, some of those same folks came up to us and said, “This actually turned out really nice. It’s good for the neighborhood.”

So yeah, in affordable housing projects, our design philosophy is still there,

but sometimes the process is more about navigating resistance and showing, over time, how thoughtful design can shift perceptions.

In recent years, there’s been a lot of discussion, especially in Europe, around the concept of the “15-Minute City,” the model developed by Carlos Moreno, where the idea is that all essential services, like work, education, healthcare, and recreation, should be accessible within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from home. I don’t know how familiar this concept is in the U.S., but we were curious to hear your thoughts on it. Given how different urban contexts can be like in Europe, where we’re dealing with very old cities that can’t change that much physically, and in the U.S., where distances are much bigger. Do you think this kind of model is applicable in your work? Or more broadly, how do you think about the principle of proximity when designing more liveable and human-centred urban spaces?

I think the idea of the 15-Minute City is definitely plausible here in the U.S., at least in many places. We don’t really face the same constraints as some European cities, like unearthing antiquities every time you dig. Sometimes we do come across historically significant sites, especially related to former tribal communities, but that’s quite rare.

That said, we do face our own unique challenges in trying to create more walkable, human-scaled environments. There have been various urban planning movements here, like New Urbanism or Landscape Urbanism, that, in a way, echo the same goals as the 15-Minute City. It's about making neighborhoods more livable, more accessible, and less car-dependent, even if we don’t always label it the same way. And while the 15-minute timeframe is actually quite reasonable when you're thinking in terms of walking, biking, or transit, not like New York where everything’s within five minutes, it becomes more complex in areas where job centers are far from where people live. That’s a big issue in many parts of the U.S.: we’ve built these sprawling cities with distinct zones for living and working, and that separation makes the 15-minute model harder to apply.

There’s also been some pushback on the concept here. In certain places, people see it as part of a political or social agenda, which complicates the conversation. But the irony is that the logic behind it, reducing car dependency, increasing access, supporting local economies, is really hard to argue against.

Take Long Beach, for example. It might surprise people, but it's actually the fifth most densely populated city in the U.S. It’s pretty built out, between the port, the airport, and established neighborhoods, there’s not much empty land. And many parts of Long Beach already have the ingredients for a 15-minute neighborhood, especially if you’re not factoring in job locations.

But nearby cities like Cudahy, Bell, or Garden Grove are even denser in terms of residential population. The issue there is they might not have job opportunities within the same proximity, so you still have people commuting long distances.

That’s a fundamental challenge here: the mismatch between where people live and where jobs are concentrated.

There have been some interesting shifts, though. Irvine, for instance, started rezoning office parks to include residential space because they were struggling to attract startups. Startups wanted to be close to where their employees lived, or vice versa. So there’s a growing realization that proximity matters, even from an economic development standpoint.

At the same time, we also have to consider zoning and health, like not placing industrial areas too close to homes, which still makes sense for safety and pollution concerns.

So, to sum it up, I do think 15-Minute Cities are achievable here, both in existing communities and in new developments. But to make it work, we need to address some key missing pieces, especially job proximity. Even with hybrid work models, people still commute a few times a week, and that adds up. The vision is possible, it just requires adapting the model to our local context.

Is there a dream project or a visionary kind of context you’d love to see City Fabrick working in someday? Something you haven’t tackled yet, but you’d really like to explore?

Well, honestly, I feel like I’ve already had the chance to work on what many would call a dream project. Right now, we’re involved in a major initiative in West LA, where we’re helping transform part of the Veterans Affairs medical campus, a National Historic District, into a supportive housing community for formerly homeless veterans. It’s a huge undertaking: 1,600 homes that could realistically cut veteran homelessness in LA County in half. It’s high-profile, complex, involves adaptive reuse, historic landscapes, existing infrastructure, really the kind of layered challenge that’s both meaningful and exciting to take on.

I’d love to do more projects like that. Ending veteran homelessness is something we absolutely can do with the right resources and the right models, it's achievable.

Another area we’re really passionate about is freeway removal. We’ve made progress on two sites in Southern California, on one in particular, I think it's just a matter of time before it happens. I'd love to see more momentum around that. Dismantling freeways opens up so many possibilities for reclaiming urban land, healing neighborhoods, and reconnecting communities that have been divided for decades.

So in a way, I’ve been lucky to already be working on the kinds of transformative projects I used to dream about. But looking ahead, I think the bigger aspiration is about scaling this work. For example, there are dozens of federally owned VA campuses across the country, in cities like Chicago, Madison, Philadelphia, that are underused and full of potential. If we can share what we’re learning here in LA, empower other teams, developers, and communities to take that model and apply it locally... then maybe we can spark real, national impact. That’s the kind of vision we’re chasing now. I mean, there are definitely interesting projects that come up and really catch our attention. We’re fortunate in that way, many of our community partners work with multiple design teams, but we’re often called in for the more nuanced, complex projects. Sure, these can sometimes bring anxiety, but they also spark great joy and incredible creativity.

So, yeah, we feel really lucky to have those kinds of opportunities. And luckily, I think we’re proving our value, because our partners keep coming back to us with these tough nuts to crack. It’s a sign that we’re on the right path, and it keeps pushing us to grow and do even better work.

I think what really stands out is how you tell your story and how City Fabrick presents itself. It’s the creativity in finding solutions and engaging people, that really shines through in your website and the stories you share. That’s definitely what caught our attention and made us eager to learn more. But now, last question, I promise! We always like to ask for recommendations movies, books, magazines, articles, podcasts, or people to follow. Could you share a couple of things you think would be interesting for us and our audience?

Yeah, for podcasts, definitely 99% Invisible, it’s all about the hidden stories behind the things you don’t usually notice in a city.

There’s also a book called The City and the City, which even had a TV adaptation. It’s a fascinating story about two distinct communities living in the same city but completely unaware of each other, kind of like parallel worlds. It’s been a while since I read it, so I might not have every detail right, but it’s a really thought-provoking concept.

Then there are some classics like the documentary Urbanized, which is pretty accessible and a great intro to urban design.

And I’d add The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs, hugely influential in North America. It would be interesting to see how it resonates outside the continent, since it’s very focused on North American urban history and community development, but I think there are valuable insights for anyone interested in cities.

So, I’d say 99% Invisible and The City and the City are great for a broad audience, while Urbanized and Jacobs’ book might appeal more to people looking for something deeper.

Discover how City Fabrick is making a differencehttps www.cityfabrick.org

Read more